Published originally in Spanish in El Salto, 29 August 2024

Adding an additional option to the gender markers on documents would mean accepting a hierarchy that is worth questioning. The author of this text, whose case has opened a crack in the Foreigners' Registry, reflects on the possibilities of a future without gender checkboxes.

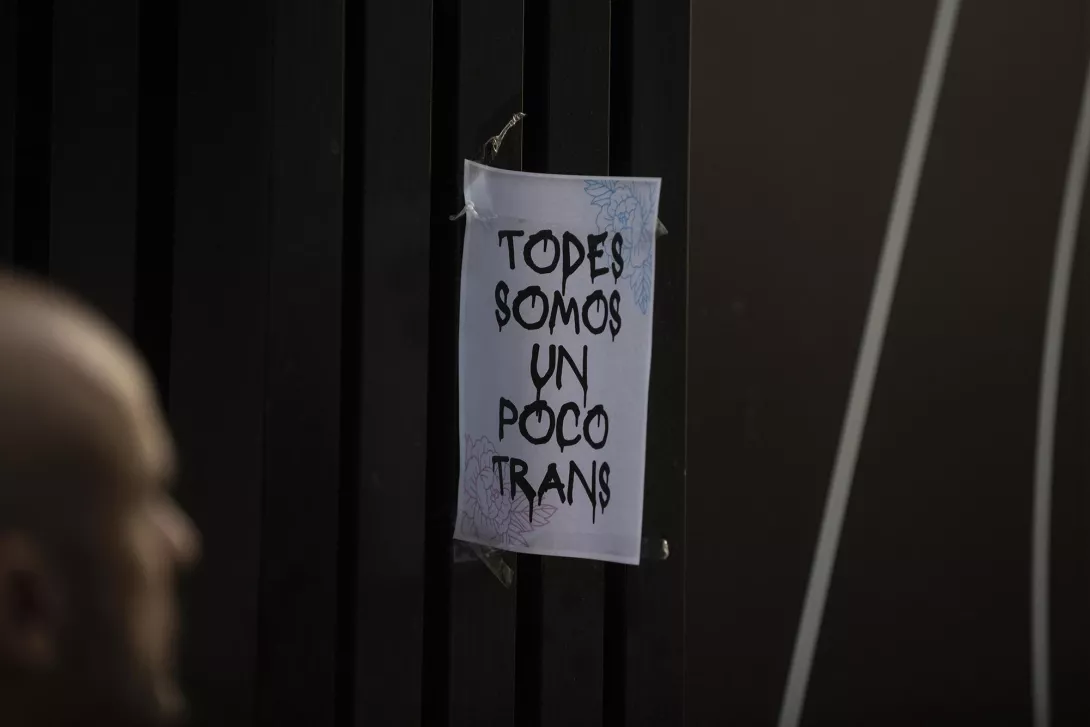

On 2 March 2023, the new trans law came into force, a law that left us, the non-binary people, out. Although the law achieved depathologization and allows to change the registered sex - that is, within the male-female binarism - through a simple administrative process, it did not achieve the inclusion of a third gender marker for non-binary people or other people who do not identify themselves within the binarism.

I myself fought in court for the recognition of my non-binary identity, as I have it registered in my passport from my country of origin. I succeeded with a groundbreaking judgment of the High Court of Justice of Andalusia in January 2023. But is this really what we want, a third box, and that's it?

Not really, at least this is not what I want. We add a third gender marker, and, obviously, this marker is going to be placed in the existing hierarchy, probably in the lowest position. And, with this, private companies can flood us with ads specifically for non-binary people: the latest “androgynous” fashion, gender-affirming surgery through private health care... No thanks!

I always understood my legal fight for my recognition as a tool to open a crack in the binary gender system, with the broader goal of destroying the whole hierarchical gender system.

I see the third gender marker only as a step towards a decertification of sex/gender, that is, the elimination of sex/gender from the civil definition of a person: from the birth certificate, identity cards, driver's license, from all "personal" data of a person. Nor would it be enough just to omit the mention of sex/gender in the national ID card, but keep it in the civil registry and in all administrations (and almost all private companies), as requested by an unsuccessful amendment of Unidas Podemos and other parliamentary groups in November 2022.

The elimination of sex/gender as a vision

Is it utopian to think of the elimination of sex/gender as a vision? Perhaps yes, but without utopias we will not change the world. And, perhaps, not as utopian as it appears.

For example, the United Nations independent expert on the protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity expressed in his 2018 report “significant doubts about the actual need for the widespread display of gender markers in official and unofficial documentation.” Principle 31A of the 2017 Yogyacarta+10 Principles also calls for “ending the recording of a person's sex and gender on identity documents such as birth certificates, ID cards, passports and driving licenses, and as part of their legal personality.” The 2017 Darlington Declaration of Australian and New Zealand intersex organizations says: “The undue emphasis on how to classify intersex people rather than how we are treated is also a form of structural violence.

The broader aim is not to seek new classifications, but to do away with legal systems of classification and the hierarchies behind them.” Even Germany's Constitutional Court, in its 2017 ruling that led to the introduction of the “diverse” option, said that “the legislator could, in general, dispense with the mention of sex in civil status law.”

But, perhaps more importantly, at least according to research in the UK, removing sex/gender from civil registration is the preferred option for many non-binary people. 57% of non-binary people responded that sex/gender should be removed as a legal status and 78% agreed or strongly agreed that “identification as male/female should be removed from birth certificates.” There is, to my knowledge, no similar research in Spain. The Study on the needs and demands of non-binary people in Spain only asked who would use a third box if it were possible, and 63% responded that they would use it.

But, at the same time, one third of those interviewed saw “reconsidering the registration and use of sex for public purposes (identification documents, administrative forms, public spaces, etc.)” as one of the main challenges, followed by “addressing the legal recognition of non-binary gender realities”. When asked about the main measures to be addressed, “Eliminate gender registration from identification documents and administrative forms” came in at 16.7% before “Include a ‘third registration’ marker in identification documents and administrative forms. Accessible to anyone, without medical requirements” with 13.7%.

Are we falling short when we merely talk about a third gender marker? Perhaps a little more ambition would do us good?

In the United Kingdom, between 2018 and 2022, The Future of Legal Gender project explored the possibilities and consequences of eliminating sex/gender as a legal category. The project asked the following questions, “What would be the social, cultural and political implications of a radical change in the way state law treats people's sex and gender? What concerns, issues and challenges would such proposals raise, particularly for thinking about equality and social justice?”

In the final report of the project, the authors state: “Decertification abolishes a formal legal structure that places people from birth in unequal categories. Registering people with a legal sex, and the expectation that people will have a corresponding legal and social gender, does not just communicate what someone is – that they are this gender or sex. It also helps form their sex and gender status and how they may identify.

More generally", the authors continue, "certification as female or male contributes to wider social norms about what sex and gender mean and how they should be expressed. Treating women and men as legally distinct groups bolsters heteronormative laws, policies, and cultural

assumptions."

The authors argue that sex/gender decertification undermines the assumption that gender divisions are natural, legal or desirable, and supports diverse forms of self-expression and interaction by softening the force of gender norms and expectations.

For people who fall outside gender norms, decertification would end the need for legal transition, or, as the authors put it, reduce “the costs and penalties faced by people whose sex or gender does not conform to current legal expectations” (trans, non-binary, intersex people).

Four challenges related to the elimination of sex/gender

I already hear the cries of “erasure of women”. But does the identity of those who utter such cries depend on a legal assignment at birth? No one is proposing to ban identification as women. But, more seriously, it is obvious that the elimination of sex/gender as a legal category would pose certain challenges.

One of those challenges has to do with statistics. Because eliminating sex/gender as a legal category is not going to end inequality and patriarchal structural discrimination against women, and other “non-male” identities, I would add. On the contrary, it could camouflage this discrimination, and it seems important to have data that make existing inequalities and discriminations visible. However, data collection by the state not only describes a reality, it also produces it.

According to Foucault's theory of biopower and biopolitics, the state's gaze - the multitude of ways in which it produces knowledge about its subjects - becomes a strategy of power in itself. Ben Collier and Sharon Cowan say in an article published in Social & Legal Studies that “subsequent developments of the concept of biopower emphasise how the categories through which data are collected have the power to shape populations both at the micro and macro level, as people are made to fit themselves into particular categories and thus reinforce the values and ideas which underlie these systems of categorisation”.

While collecting data on individuals and groups can cause harm to individuals and communities, not collecting data can also cause harm when the state deliberately or for lack of resources leaves these groups unprotected. This, for example, happens to already marginalized groups, such as the non-binary collective. The collection of sex/gender data with two categories - male and female - again makes us invisible, and camouflages the inequality and structural discrimination we suffer.

Statistics are needed to build policies to counteract inequalities and structural discriminations. The question is: What data are needed to make visible these inequalities and discriminations with all our intersectionalities? Is the routine collection of data by the Tax Agency, the Social Security, the Register of Inhabitants, based on gender identity according to the civil registry, useful? In these data collections it remains hidden that 80% of trans people are unemployed, for example. If we want statistics that help us develop social policies to address inequalities, we need statistics that take into account the realities and intersectionalities of people, and that is developed in consultation with affected communities.

The second challenge has to do with how sex/gender anti-discrimination measures would be articulated. In both the UK and Spain there are laws that prohibit any discrimination (the Equality Act 2010 in the UK, Law 15/2022 of 12 July, comprehensive law for equal treatment and non-discrimination in Spain).

For example, in Spain, the law prohibits any discrimination “on the grounds of birth, racial or ethnic origin, sex, religion, conviction or opinion, age, disability, sexual orientation or identity, gender expression, disease or health condition, serological status and/or genetic predisposition to suffer pathologies and disorders, language, socioeconomic status, or any other personal or social condition or circumstance”. Of this long list, only sex is a legal category. In other words, it is possible to legislate against discrimination even though there is no legally defined category that is part of a person's marital status. The same is the case with hate crimes, which are applicable to hatred based on religious beliefs, sexual orientation, racial or ethnic origin and more categories without expression in the civil registry.

A third challenge leads us to the question of what would happen to sex/gender segregated spaces. Can we have these spaces when sex/gender no longer exists as a legal category? Leaving aside the debate about the problems that binary sex segregation causes for us non-binary people, an article by Flora Renz, Gender-Based Violence Without a Legal Gender: Imagining Single-Sex Services in Conditions of Decertification, published in the journal Feminist Legal Studies, explores the question. Her article is based on interviews with employees mainly from local authorities or NGOs providing services for women victims of gender-based or domestic violence in the UK.

In contrast to Spain, in the UK there is no national ID card, and simply for practical reasons service providers are generally unable to check the legal sex/gender of the person - who usually carries their birth certificate with them? The vast majority of respondents report using the victim's self-definition, and most are also trans-inclusive.

Although the law prohibits any discrimination, more important for the provision of services for a single sex - usually women - is when “discrimination” is permitted. Article 2 paragraph 2 of the law says: “Notwithstanding the provisions of the previous paragraph, and in accordance with the provisions of Article 4 paragraph 2 of this law, differences in treatment may be established when the criteria for such differentiation are reasonable and objective and what is pursued is to achieve a legitimate purpose (...)”.

In other words, although sex/gender discrimination is prohibited, there are good reasons why it is necessary and legitimate to exclude men (cis) from certain services for victims of gender or domestic violence. But, this does not necessitate that sex/gender be listed on the ID card or birth certificate.

Flora Renz says: “Although services currently don’t generally require formal legal documentation to evidence someone’s gender there is nevertheless a question to what extent current practices are based on an implicit assumption that woman/man are largely stable and coherent categories. As noted above, decertification might see the criteria that organisations use to determine who can access services, and therefore who for their purposes is a man or a woman, shaped by both judicial and political interventions. While it is possible to imagine that decertification could lead to the development of a huge range of different ways to define various kinds of genders, it seems more likely that at least in the context of equality law over time there would be a formalisation of some commonly accepted ways of defining genders, perhaps along similar lines of division as religious groupings with some taking a more ‘liberal’ approach (e.g., self-definition) while others default to a kind of gender orthodoxy, by relying for example on biological characteristics over social ones.”

And what would be the problem with this? Do we really need a single definition of sex/gender? Couldn't there be different definitions depending on the context?

In her conclusions, Renz calls for caution: “Any move towards decertification would need to be highly attentive towards the structural underpinnings of gender, and in particular the ways in which they continue to have a disproportionate negative, and at times explicitly violent, effect on some groups over others, particularly women, disabled people, racialised minorities and those whose gender has historically not been supported by the state and civil society.”

The fourth challenge challenges the healthcare system. At your health center, the information about your registered sex says very little. It says nothing about the body you have, nor does it say how you prefer to be treated. The authors of the final report of The Future of Legal Gender project say: “For medical purposes, good practice involves asking questions with a higher level of specificity. For example, “Do you menstruate?” rather than “What is your sex?” because the sex category elicited by this question may not provide useful information about the body someone has.”

For example, a trans woman is most likely going to identify as a woman (even now, at least if she has changed her registered sex). This says nothing about her body. Or, I myself am registered with the Andalusian Health Service with “sex not specified”, which also says nothing about my body (even in my annual blood test there is a value that cannot be calculated due to lack of binary sex information), and it also says nothing about the pronouns I use. For the health system to have useful information, they should record that I have breasts and also a prostate. Then they would have relevant information about my body and could alert me to early detection campaigns for breast cancer and prostate cancer. Now I don't receive anything. And they should also record how I prefer to be addressed: in my case, in neutral gender and the pronouns they/them.

Let's dream: for a world without legal sex/gender

I am convinced that we need dreams. Utopias that, perhaps, will always remain utopias, but that motivate us, that guide us to build a better world. For me, fighting for a third gender marker, which I have obtained in the Central Registry of Foreigners, was always a way to open cracks in the gender system, but it was never meant as an end as such.

Removing sex/gender from the Civil Registry - from birth certificates, from the National ID card, from the driver's license, from any documentation - is not going to end patriarchy, inequality and structural discrimination based on gender identity. I am not naïve.

But, as the authors of the final report of The Future of Legal Gender project say: “The de-linking of sex and gender from legal status also contributes to the dismantling of a normative structure that shapes people's lives and identities. The ambition of decertification is that it can contribute to reducing gender-based socialization and encourage greater variation in the way people live, appear, and express themselves, in ways that are less conditioned by gender norms (as well as less conditioned by the state).”

Or, as Benny, one of the non-binary people interviewed in the research on the perspectives of non-binary people, says about eliminating legal sex/gender: “If we have a choice, it would be the best thing, because the fact that it [legal gender] exists is what causes the problem. It really is. It's ingrained in ways of describing people who are not men, and we don't need it. I wish we could do it. It sounds like an impossible dream. I wish we could.”

Maybe this dream is not so impossible. I hope it isn't.

- Log in to post comments